Cities

The project is structured around a transnational in-depth comparative case studies located in Vienna, Marseille, Prague, and Glasgow, engaging with local stakeholders and communities. The compared cities and case studies should allow us to approach historic housing as cultural heritage adaptation and transformation to climate change in different ways while formulating general upscaling recommendations.

The transnational approach is supported by an interdisciplinary team and provides a basis for an iterative comparison by upgrading knowledge from the different case studies and testing it on Zürich.

Prague

Area: 496.2 km²

Population: 1,397,880 inhabitants (as of 31 December 2024)

Population density: 2,817 inhabitants/km²

As of 2021, Prague had a total of approximately 628,000 dwellings, of which:

- 10.5% were built before 1920

- 31% were built before 1946

Out of approximately 98,000 houses recorded in 2021:

- 9.4% were built before 1920

- 34.5% were built before 1946

Gentrification: renovated house in Prague 10 - Vršovice

(photo Matej Martinak)

Prague’s urban landscape reflects a rich and complex layering of historical periods and political regimes, each leaving a distinct mark on its housing stock and spatial structure. While the UNESCO-listed historic core—comprising the Old Town, New Town, Malá Strana, and Hradcany—preserves the city’s medieval foundation, much of present-day Prague has been shaped by 19th–20th century industrialisation, socialist-era planning, and post-socialist transformation.

The city’s population has been steadily growing since the mid-19th century. Its most dynamic expansion occurred between the late 19th century and the 1930s, when urban modernisation spurred the development of dense residential neighbourhoods encircling the historic centre—such as Vinohrady, Zizkov, Smíchov, Karlín, and Holešovice. These districts are characterised by five- to six-storey tenement blocks arranged around shared courtyards, built in architectural styles ranging from historicism and Art Nouveau to early modernism and Czech cubism. With mixed-use ground floors and walkable layouts, these quarters remain largely intact and are considered highly sustainable. Unlike in many Western European cities, they were not widely demolished in the 20th century.

Prague 2 - Vinohrady (photo Matej Martinak)

During the socialist era (1950s–1980s), large prefabricated housing estates—such as Jižní Město, Prosek, and Cerný Most—were constructed on the urban fringe to address acute housing shortages. While architecturally uniform, these estates now accommodate over a third of Prague’s population and continue to provide key public infrastructure and green spaces. At the same time, much of the inner-city housing stock was labelled unfit for habitation. Between 1950 and 1991, the city’s population grew by just 14.8%, a slower pace compared to previous decades.

Since 1990, Prague has experienced fragmented, market-driven urban development. Gentrification and the redevelopment of former industrial areas have reshaped inner-city districts, while rapid suburbanisation has led to significant population growth in the metropolitan hinterland. New residential areas have predominantly served upper-middle-class households, and the absence of comprehensive planning has contributed to soaring housing costs. Affordability has become a major concern, underscoring the tensions between heritage preservation, spatial equity, and contemporary urban growth.

Prague 3 - Žižkov (photo Matej Martinak)

Today, 31% of Prague’s housing stock was built before 1946 and is classified as historic—mainly concentrated in inner-city multi-apartment blocks. The remaining 69% is modern: 42.9% was built between 1946 and 1990 (primarily prefabricated estates), and 26.1% after 1991.

In terms of tenure, 50.6% of homes are owner-occupied—either single-family houses (10%) or apartments in homeowner associations (35%) and cooperatives (5.6%). Rental housing accounts for 32%, though only 4.8% is publicly owned by the city. The remaining 17.4% consists of other or unspecified forms of tenure.

Vienna

Area: 415 km²

Population: 2’005’760 inhabitants

Population density: 4.778 inhabitants/km²

From the total 165.000 buildings,

32.442 (20%) buildings were built before 1919.

Wien in Zahlen, City of Vienna, Statistik Austria, Jan. 2023

Lageplan & Schwarzplan von Wien, DWG Plan, schwarzplan.eu →

Vienna’s Historic Housing Stock

Vienna’s historic housing stock is the outcome of the rapid urbanization and industrialization that took place between 1848 and 1918, a historic period described as the Gründerzeit. In this historic period, Vienna’s population grew from about 0.5 million to more than 2.2 million (Weigl, 2003). The Gründerzeit was shaped by an enormous degree of construction activity, whereby the state provided technical and social infrastructures (water supplies, public spaces, transport, schools, …), while housing provision was determined by the free market, only regulated by building legislation (Bobek & Lichtenberger, 1966). At the time, legislation stipulated a strict block-grid as well as a construction height that allowed for five floors in the inner city and two or three floors in the peripheral city districts. In the era of industrialization, the housing situation was characterized by important social contrasts: one could find bourgeois tenement houses with large apartments close to the city centre on the one hand, opposed to working-class houses on the other, dominated by two- or three-roomed apartments, with water access provided only on the corridors.

Plan Wien, 16th, Map of the Ottakring district (part east),

Wien Museum Online Collection 233734/2, CC0

The outcome of this period is a compact urban core, which encloses the historic city centre in a radius of 3 to 5 kilometres. This area comprises various qualities. Firstly, from an architectural perspective, brick is a ‘soft’ building material that allows a high adaptability to changing social and technical requirements. Furthermore, rooms generally are between 3.2 and 4 metres high and even beyond, which is today considered as a special high quality of living. Secondly, from an urban planners’ perspective, the Gründerzeit city displays high functional diversity, which correlates with up-to-date concepts of urban development, such as the ‘compact city’ or the ‘city of short distances’ (Glaser et al., 2013). Thirdly, beyond these architectural and urbanistic qualities, housing-policy implications of this historic housing stock are also relevant, as the rents are highly regulated (Mietrechtsgesetz, MRG). Due to the combination of affordable rent prices and a private, low-threshold access to housing, this historic housing stock often provides the first access to the housing market in Vienna for intern and international persons.

Fig.1 Sperlings Postkartenverlag (M. M. S.), Johnstraße 21-23, 1900-1905,

Wien Museum Online Collection 234706, CC0

Fig.2 Martin Gerlach Jun., Kolinggasse 18, After 1938,

Wien Museum Online Collection 26975, CC0

These historic tenement buildings – also called Zinshäuser in Vienna – displayed a very low profitability for decades until the 2000s, during which the market situation changed fundamentally. During the house price boom in Vienna (2007 and 2022), a gap rose between regulated rent prices and purchase prices. This gap between MRG-regulated rents and apartment selling prices triggered the circumvention of MRG-rents, which has become a highly profitable business. This circumvention could take place in two ways (Musil et al., 2022): Firstly, by the demolition of existing objects and the construction of new residential buildings that would not be MRG-regulated and furthermore contain more apartments (physical conversion). Secondly, by the legal (or tenure) conversion of existing objects into condominium houses, in which all apartments were to be sold individually on the ownership market. Additionally, the roof trusses of the converted houses have often been converted into high-priced penthouses. Due to these two forms of conversions, the traditional Zinshäuser in Vienna have become a highly profitable ‘money machine’ and as such strongly desired objects for developers.

Fig.3 Transformation: Musil, Brand and Punz 2022

The contradiction between this market constrains, the increasing demand for affordable housing and the need to implement climate mitigation and prevention strategies (cooling, greening, decarbonization…) is the main challenge for the Viennese historic housing stock.

Zurich

Area (City): 87.88 km²

Population (City): 448.664 inhabitants (2024)

Population density (City): 5.105 inhabitants/ km²

Area (Canton): 87.88 km²

Population (Canton): 448.664 inhabitants (2024)

Population density (Canton): 5.105 inhabitants/ km²

Out of 54.378 buildings in Zürich, approx. 12.000 (22%)1 were built before 1920 and 17’590 (32%) before 19302 (2023).

(1) Historical Monuments Archive of the City of Zurich, SMAPSHOT - Stadt Zürich, Amt für Städtebau →

(2) City of Zurich →

Photograph taken between 1900–1909 in the Wipkingen district of Zürich shows the building activity in this period.

Zurich underwent rapid development in the period from 1850 to 1920. The former Schanzenzone (moat) provided space for new transport routes and the first growth ring: the main railway station and city centre on Bahnhofstrasse, residential palaces and buildings for administration and culture on the new quays, the university and hospital district on the hillside terrace on Rämistrasse. Villa neighbourhoods were built on the sunny slopes and industrial zones and working-class districts on the Sihlfeld plain. Founded in 1855, the Swiss Federal Polytechnic with its construction and engineering school and its international recognition had a large impact on these developments.3

Zurich’s historical building stock dating before 1920 makes up about 22% of its overall building stock, which also corresponds to the statistics for Switzerland in general.4 The building activity between late 19th century until the 1920 and to 1930s has been critical in shaping the quarters of the city around the old city (Niederdorf, District 1). Approx. 10% of this building stock is protected.

Typical brick façade of the 19th century in Zurich (Photo: Stefan M. Holzer, 2017)

Source: Facing Bricks in Zürich (1884-1914) →

Zurich provides a particularly impressive case study of a city with a rich still-preserved stock of brick-faced buildings from this boom period. With the exception of a few details, the types of buildings and constructions found here are largely exemplary of the fin de siècle design and construction trends that left little room for regional differences, at least in the German-speaking world. However, Zurich is a particularly striking example for a study of the veneering technique of the late 19th century. In contrast to many German cities, the city on the Limmat was spared the destruction of the two World Wars, so that entire districts from the construction phase of the late 19th century are preserved with a high proportion of original substance.5

(3) Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte (Ed.) Zürich. Architektur und Städtebau 1850–1920. ISBN: 978-3-280-02817-9, GSK – Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte →

(4) Federal Statistical Office →

(5) Facing Bricks in Zürich, research project at the Chair of Building Archeology and Construction History, ETH Zürich

Marseille

Area: 240 km²

Population: 873’076 inhabitants

Population density: 3 628,4 inhabitants/km²

Over 40% of residential buildings were built before 1920.

Marseille is the second-largest city in France. Its historic urban fabric reflects the major periods of its development since the 17th century. As a port city turned towards the Mediterranean, it has inherited a cosmopolitan character from its history (Roncayolo 2014; Temime 1995).

The city's social structure is characterised by strong inequalities, a high poverty rate (25% in 2020 compared with 14.6% nationally) and a high unemployment rate (Insee, 2023). Impoverished neighbourhoods are concentrated in its central and northern sectors. The historic city centre is also composed of socially mixed and wealthier neighbourhoods to the south and the east. In the last years, analysis of socio-spatial evolutions in Marseille’s central neighbourhoods shows « simultaneous processes of gentrification and impoverishment » (Bouillon, Baby-Collin, et Deboulet 2017).

Fig.1. Household available median incomes per consumer unit (Source: Bergerand 2024)

Vernacular architecture in the historic city centre mainly dates back to the 19th century (Fig. 2). Buildings were designed for mediterranean climate, allowing natural ventilation, double sun exposure of units, protection against strong winds, etc. (AGAM 2024; Bonillo et al. 1988). However, changes made to the buildings throughout the years, evolutions in the ways of living and climate change raise new issues around the livability of this housing stock. Today, the city centre is partly classified as a Remarkable Heritage Site, this perimeter aims to preserve urban and architectural heritage within a defined area around the Old Port (Fig. 3 and 4).

Fig. 2. Marseille in the the 19th century. Source: gallica.bnf.fr → / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig. 3. Remarkable Heritage Site perimeter and main architectural typologies. Source: Groupement Indiggo, Marseille 2030 - coeur historique en transition, p.55

Fig. 4. Marseille’s Old Port, Author: Saïd Belguidoum

Five historic architectural types can be broadly identified in different parts of the city centre : 17th and 18th century houses, late 18th and early 19th century “three-window buildings” (Fig.5), large 19th century haussmanian-style tenement buildings (Fig.6), large mid-20th century tenement buildings (Art deco and Art nouveau styles) and post-war Modern architecture.

Fig. 5. Variations on Marseille’s ‘three-window’ architectural type. Author: Saïd Belguidoum

Fig. 6. Haussmanian-style architecture. Author: Saïd Belguidoum

Central neighbourhoods are mainly composed of private rental housing, with a majority of small apartments built before 1949. Housing deterioration is a major issue as 35 % of homes are considered to be substandard in these central districts. Housing issues focus new attention since three buildings collapsed in 2018, leading to the death of 8 tenants and to an important wave of evictions across the city - 600 buildings were evacuated between 2018 and 2021, especially in the poorer neighbourhoods (Dorier 2022).

This historic housing stock is also subject to transformations as market dynamics evolve. Housing prices in Marseille remain lower than those of other major French cities. They have however risen since the early 2000’s and again since 2016, and some central neighbourhoods are more strongly impacted (DV3F, Cerema). New investment strategies, linked to price increases and gentrification trends, emerged in these neighbourhoods in recent years, such as conversion of homes to short-term tourist accommodation.

The global deterioration of the housing stock is one of the main focuses of housing policies today in Marseille’s city centre. Prioritization of security issues has sometimes led to demolitions, but public action is steered towards retrofitting the historic housing stock through social housing production and incentives to private stakeholders. Renovations rely on a new public player, a public development company, which aims to provide an exemplary retrofitting model with careful consideration to environmental quality and heritage preservations. Costly for public authorities, this model cannot be replicated indefinitely. Outside of this limited scope of action, on the one hand, a majority of the housing stock in the city centre is composed of small private co-owned apartment buildings, with few tools to insure global renovations integrating both environmental and affordability issues in the long run, especially in a context of increasing rental and property prices. On the other hand, in some areas, demolition of ordinary heritage can be considered when local authorities prioritize densification, real estate developments or transport infrastructure.

In the face of climate change, Marseille’s dense historic centre is particularly at risk from heat waves, it is also vulnerable to droughts and floods due to run-off and rising sea levels (Groupement Indiggo, 2023). Climate change adaptation policies such as permeability restoration, cooling, renaturation, comprehensive rehabilitation, etc. are still in their early stages. Reconciling issues relating to climate emergency, structural safety of buildings and housing affordability is a major challenge for Marseille’s historic centre.

Fig. 7. Mineral public spaces in a dense urban fabric

Author: Saïd Belguidoum

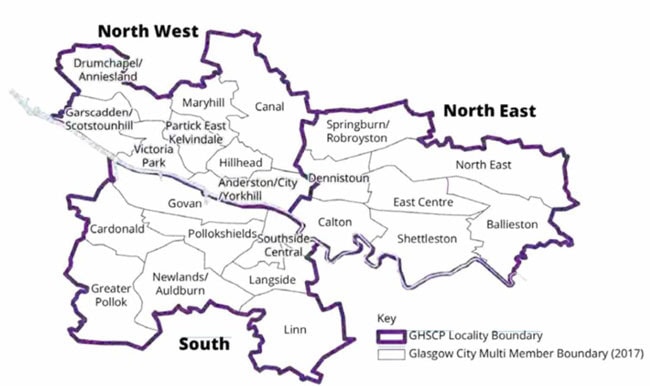

Glasgow

Area: 175 km²

Population: 622,050 inhabitants

Population density: 3,562 inhabitants/km²

Around 25% of residential buildings built before 1919.

Glasgow (Glaschu in Gaelic, meaning Dear Green Place) is the largest city in Scotland. The city is built around the banks of the River Clyde which enabled rapid internationalisation of manufacturing and shipbuilding and accelerated the development of the city’s historic housing stock to accommodate factory workers and their families.

Fig. 1. Historic Plan of Glasgow, 1912. National Library of Scotland (2025)

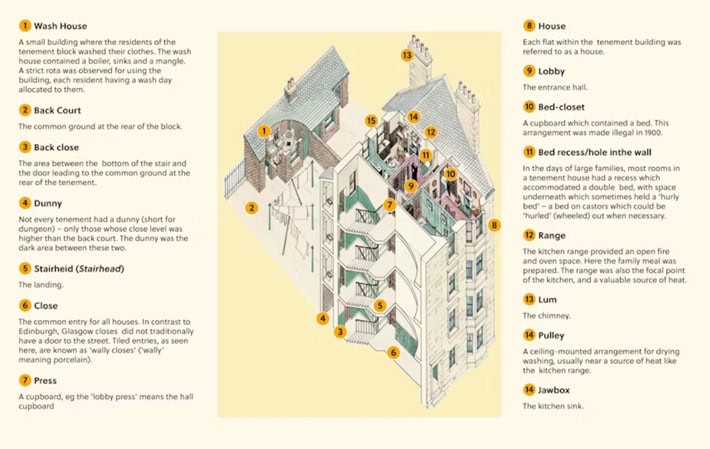

The Growth of Glasgow’s Tenement Buildings

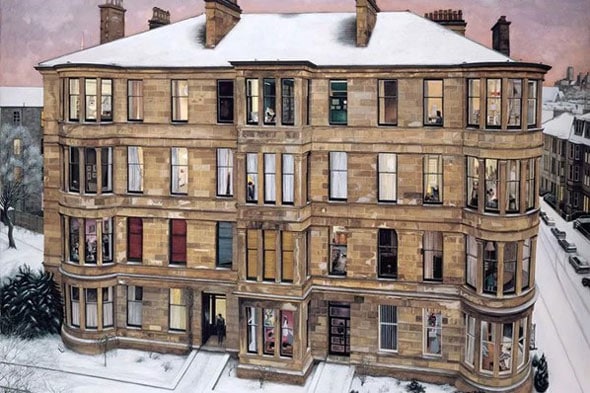

Tenements were first built in the city in the 1700s but the style of building took prominence between 1850 and 1915 when the city experienced a cultural and architectural boom. Famous Scottish architects Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson and Charles Rennie Mackintosh designed unique housing and commercial buildings that can still be seen across the city today. Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson incorporated Greek, Egyptian and Mediterranean styles and pioneered a sustainable approach to building by considering the well-being of those who would inhabit his buildings and embracing new technologies and materials such as cast-iron moulds and glass plates. Tenements were constructed using locally sourced blonde sandstone and red sandstone from Dumfriesshire and constructed to be four storeys tall, never taller than the width of the street, and built in blocks along streets inner-city areas creating the city’s distinctive grid pattern that still defines the city’s urban landscape.

Fig. 2. Tenement Flats in Glasgow, Glasgow City Council (2021)

Tenements quickly gained popularity as a convenient housing solution for the burgeoning population of urban manual workers to the city during the industrial revolution of the Victorian era that saw the population grow from 220,000 to 762,000. Workers and their families migrated to the city as it became a manufacturing powerhouse for cotton, textiles, chemicals, glass, paper and soap manufacturing, later leading to shipbuilding and modern engineering. To meet the demand for housing for those working in the factories and shipyards, tenements were quickly built across the Southside, West and North-East of the city to various standards. Due to this rapid industrialisation, the location and easy accessibility of Glasgow through its ports and railway systems, the city quickly developed a global trade network and became known as the Second City of the Empire.

Fig. 3. Schematic Map of Glasgow Area Boundaries

Division of Social Classes

While tenement buildings were built to accommodate a variety of classes and the look and composition of the buildings across the city appeared uniform, there was a disparity of size and quality across different parts of the city, the impacts of which continue to create structural and cultural divisions today. On one hand, middle-class tenements housed the city’s professionals and featured multiple rooms and luxuries such as private bathrooms. In stark contrast, the working-class tenement consisted of a high rise of single room apartments (referred to as a ‘single-end’) that housed families of up to 8 people. While this created a sense of community in the “closes”, communal stairways or passageways between flats, overcrowding and poor sanitation were common issues in these tenement buildings leading to outbreaks of diseases such as cholera. These poor living standards led to tenements being demolished in the worst affected areas in the East and South of the city after the second world war and replaced with other forms of housing such as high-rise flats.

Fig. 4. Schematic diagram of The Tenement House, National Trust for Scotland (2025)

Tenement’s Historical and Cultural Significance

Tenements have evolved from a practical necessity in the 19th Century to an iconic part of the city’s historic and cultural identity, resulting in the definition of a tenement being written into Scots law. Section 26 of the Tenement (Scotland) Act 2004 defines it as “two or more related but separate flats divided from each other horizontally”. They are also prominent in national poetry and art including Windows in the West by Avril Paton (1993) one of Scotland's best-loved paintings. It is this fondness for the tenement and its Victorian architecture and features including large bay windows, high ceilings and fireplaces, that make these properties highly sought after by homeowners in the affluent Westend and Southside of the city

Fig. 5. Windows in the West Avril Paton (1993)

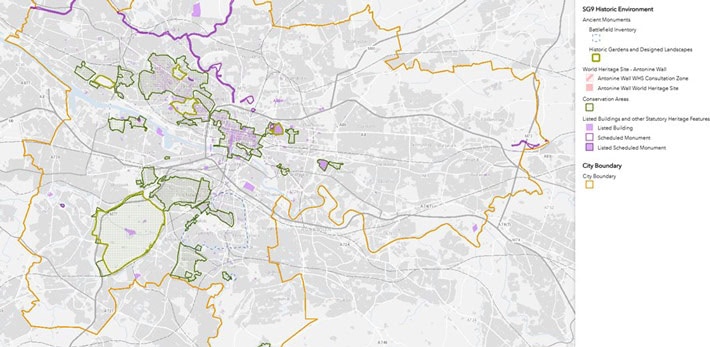

Areas of Conservation

The historical and cultural importance of tenement buildings and associated architecture across the city have resulted in the protection of several Conservation Areas, defined as “an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance”. In 1972, Glasgow West was designated the first Conservation Area in the city and in 1975, Hyndland was given its own special designation, the only one in the UK. This means that these tenements can never be demolished and replaced with new builds. Key features that are protected as part of the Conservation Area include the street pattern, building line, original architectural and townscape details, the architectural quality of the Victorian tenements and other housing and buildings, and the use of traditional materials including the timber sash and case windows and cast-iron railings, defining features of tenement housing in the city.

Fig. 6. Glasgow GIS map of conservation areas

Figs 7 and 8. Broomhill tenement housing protected by Conservation Area

Addressing Climate Change Challenges in Tenement Buildings

While Victorian features make these buildings highly sought after and therefore expensive, they have negative consequences that weren’t considered during their era of construction, resulting in high costs of living in and caring for these buildings. The protected single-glazed sash windows, high ceilings and stone walls provide poor insulation in a city well-known for its cold weather, resulting in high energy use by the more affluent population who can afford to heat their homes in these buildings, and poor health of those who cannot. Therefore, while these homes are cared for and sought after in the affluent areas of the North West and South of the city, they are dilapidated and unfit for purpose in the East of the city, creating a stark contrast in neighbourhoods as you move through these different areas.

References

- BBC (N/A) The Victorian Achievement, History Trails [online]. Available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/scottishhistory/victorian/trails_victorian_glasgow.shtml [Accessed July 2025].

- Campbell, R (2025) Tenements: A home for the middle classes too, Glasgow City Heritage Trust [online]. Available: https://www.glasgowheritage.org.uk/tenements-a-home-for-the-middle-classes-too/ [Accessed July 2025].

- Glasgow City Council (2015) Broomhill Conservation Area Appraisal. Available: https://glasgow.gov.uk/media/1615/Broomhill-Conservaton-Area-Appraisal/pdf/Broomhill_Conservaton_Area_Appraisal.pdf?m=1668509564387 [Accessed July 2025].

- Glasgow City Council (2021). Plan to safeguard pre-1919 tenements in Glasgow [online]. Available: https://glasgow.gov.uk/article/2877/Plan-to-safeguard-pre-1919-tenements-in-Glasgow [Accessed July 2025].

- Glasgow City Council (N/A) City Development Plan: SG9 Historic Environment GIS Map [online]. Available: https://glasgowgis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=71d41d4d48214ac69135d7a441e1240e [Accessed July 2025].

- Glasgow City Council (N/A) GCHSCP Demographics and Needs Profile [online]. Available: https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/article/6371/City-Map. [Accessed July 2025].

- MacInnes, R (2004) The Glasgow Story: No Mean City: 1914 to 1950s: Buildings and Cityscape: Public Housing [online]. Available: https://theglasgowstory.com/story/?id=TGSEF11 [Accessed July 2025].

- MacMillan, A. (2004) The Glasgow Story: Modern Times: 1950s to The Present Day. Available: https://www.theglasgowstory.com/story/?id=TGSFF10. [Accessed July 2025].

- National Library of Scotland (N/A) Bartholomew Survey Atlas of Scotland, 1912 [online]. Available: https://maps.nls.uk/view/74400475 [Accessed July 2025].

- National Trust for Scotland (N/A) The Tenement House [online]. Available: https://www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/the-tenement-house [Accessed July 2025].

- National Trust for Scotland (N/A) Glasgow’s Built Heritage, The Tenement House [online]. Available: https://www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/the-tenement-house/a-social-history-of-glasgow [Accessed July 2025].

- Scotland’s Cities, Scotland (2025) [online]. Available: https://www.scotland.org/about-scotland/scotlands-cities [Accessed July 2025].

- Scottish Government (2004) Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004 (asp 11) [online]. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2004/11/pdfs/asp_20040011_en.pdf [Accessed July 2025].

- Under One Roof (N/A) Glasgow’s Tenemental Challenge [online]. Available: https://underoneroof.scot/glasgows-tenemental-challenge/[Accessed July 2025].

- Williams, C. (2022) Windows In the West by Avril Paton and the story behind one of Glasgow’s most iconic paintings. Glasgow Live, October 2022 [online]. Available: https://www.glasgowlive.co.uk/news/history/painting-windows-the-west-glasgow-19663589 [Accessed July 2025].